A marking gauge is a layout tool with precisely one function: it scribes a line parallel to an edge. Although some older gauges have been made with a ruler printed on the arm, it is far more accurate to merely set the gauge to the exact width of another object, such as a chisel or a workpiece, which can be done with literal pinpoint accuracy.

So Many Kinds of Gauges

A marking gauge is a very simple tool, consisting of three essential parts: an arm, a fence, and a cutter. Most gauges also have a locking mechanism, which prevents the fence from moving in use.

Shop-Made Marking Gauge with Captive Wedge

Many early marking gauges had no locking mechanism, and the arm was instead merely friction-fit into the fence. Once the arm wore down, a captive wedge might be retro-fitted.

Most commercially-made gauges have a thumbscrew locking mechanism, which holds well but requires two hands to set. If you like making your own tools, a captive-wedge mechanism is easy to make, and it usually requires only one hand to set. This allows you to hold the gauge to a precise setting with one hand and lock it with the other.

There are many different types of marking gauge available. The mortise gauge uses two pins to scribe two lines parallel to each other and to an edge. A panel gauge has an exceptionally long arm (sometimes over 36”) and wide fence, for large layout jobs. Some gauges even substitute a pencil for a cutter.

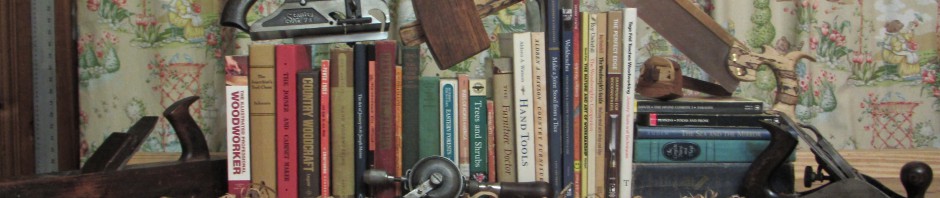

L-R: a panel gauge, three marking gauges in different sizes, and a cutting gauge

Cutters come in several different styles. The most common type is a simple pin made of steel and often filed to a knife-like edge. Other gauges use a small knife blade, and are called cutting gauges. Wheel-gauges work on similar principles, with a round cutter. Cutting gauges and wheel gauges are especially effective for scribing accurate lines across the grain, where a pin-gauge will often tear the fibers, resulting in an inaccurate line.

Most marking gauges can be either pushed or pulled, and each woodworker will likely have a personal preference for one over the other. An exception is the cutting gauge, in which the orientation of the knife blade allows the gauge to be used in only one direction.

Shop-Made Cutting Gauge (Pecan and Sweet Gum woods) with Wedged Cutter

Fortunately, the cutters are usually reversible, allowing the user to set it up for use in either direction. Cutting gauges also tend to scribe finer lines than pin-gauges, so many woodworkers prefer them for all-around use.

Scribe Your Line

A marking gauge is one of those tools that you think you know how to use as soon as you see it. Using a marking gauge effectively is very simple, but maybe not as simple as it looks. If you just hold down your workpiece with one hand and draw the pin along the wood with the other, you may well get a nice, accurate line. But the cutter may also tend to follow the grain of the wood, pushing the fence away from the workpiece, ultimately resulting in a crooked line. It’s easy to avoid this problem, if you follow these steps:

1. If possible, secure the workpiece on the bench so you can guide the gauge with two hands. This is especially important when the arm of your gauge is extended an inch or more, but with practice, it is possible to use the gauge with only one hand. When you use two hands, each hand has a separate job. One hand grasps the fence and presses it against the workpiece. The other hand pinches the arm and moves the gauge forward or back.

2. Do not begin your line at the end of the board.

Always drag the pin!

If you like to pull your gauge, as I do, begin your line a few inches from the near end. (If you like to push your gauge, that’s fine too, but you’ll have to reverse everything from here on out. Begin near the far end, and work toward the near end.)

3. Tilt the gauge toward you, and drag the pin lightly over the wood, all the way to the near end of the workpiece.

Use a light touch.

Do not press the pin down into the wood. Let the cutter do the work. You will go over this line several times in the course of scribing the line, so it should be faint at first.

First line darkened with a pencil for visibility

4. Pick the gauge up and place it forward of the scribed line a few inches, and pull it back again until you have gone over most of your previous stroke, deepening the original line. Work your way down the board like this, taking short, light, overlapping passes.

Several short, light passes are better than one long, heavy pass.

Each time the cutter begins to contact the wood, it should touch fresh wood first. If any of your strokes wanders off the line, your next stroke will correct the error rather than following it.

The pin should touch fresh wood each time you place it on the workpiece.

5. When you get to the far end of the board, you may need to reverse your cutting direction, and push your gauge to the very end. This allows more of the fence to stay in contact with the workpiece at the very end of the cut. I seldom do this, however, because the gauges I have made for myself all have extra-wide fences at the bottom, so it is easier to keep them in contact with the workpiece, even at the end.

Quick work in practice

In practice, this is a very quick procedure. Secure your work, set your gauge, and zip-zip-zip-zip-zip-you’re done. You may find that you need to darken your gauge line with a pencil so it’s easier to see.

Bonus: Scribing a Stopped Line

An advantage of the pin-gauge is that it allows you to scribe a stopped line. This is especially helpful when laying out mortises, when you seldom want your lines to run past where the wood joins. Scribing a stopped line is very easy.

1. On one end of the line, press the pin of the gauge straight down into the wood, leaving a little pinhole.

You are allowed to press the pin into the wood just this once.

2. Move your gauge to the other end, and drag the pin lightly across the workpiece until you feel the pin drop into the hole you just made. You won’t see it happen, but you’ll easily feel it.

Line darkened with a pencil for visibility

Because such lines are usually short, I usually scribe them in a single pass. Go over the line again with your gauge, or with a pencil, if you need a bolder line. Or get yourself some reading glasses.

Thanks for a great article, yet again, Sir! I didn’t realize all I didn’t know about this great tool. Good info. Tim

I’m glad to hear it was helpful. I had to figure out some of this myself through trial-and-error, but none of it is new or original information. I learned the stopped-line trick in the first woodworking class I ever took, and the rest I picked up here and there.

There is additional information here:

http://www.toolsforworkingwood.com/Merchant/merchant.mvc?Session_ID=b702f0900d52e1b33d83b0275c5af50d&Screen=NEXT&StoreCode=toolstore&nextpage=/extra/blogpage.html&BlogID=279&BG=1

and here:

http://www.toolsforworkingwood.com/Merchant/merchant.mvc?Session_ID=b702f0900d52e1b33d83b0275c5af50d&Screen=NEXT&StoreCode=toolstore&nextpage=/extra/blogpage.html&BlogID=8&BG=1

Pingback: General Tools Marking Gauge: A Review | The Literary Workshop Blog